The Morris Minor: A British miracle

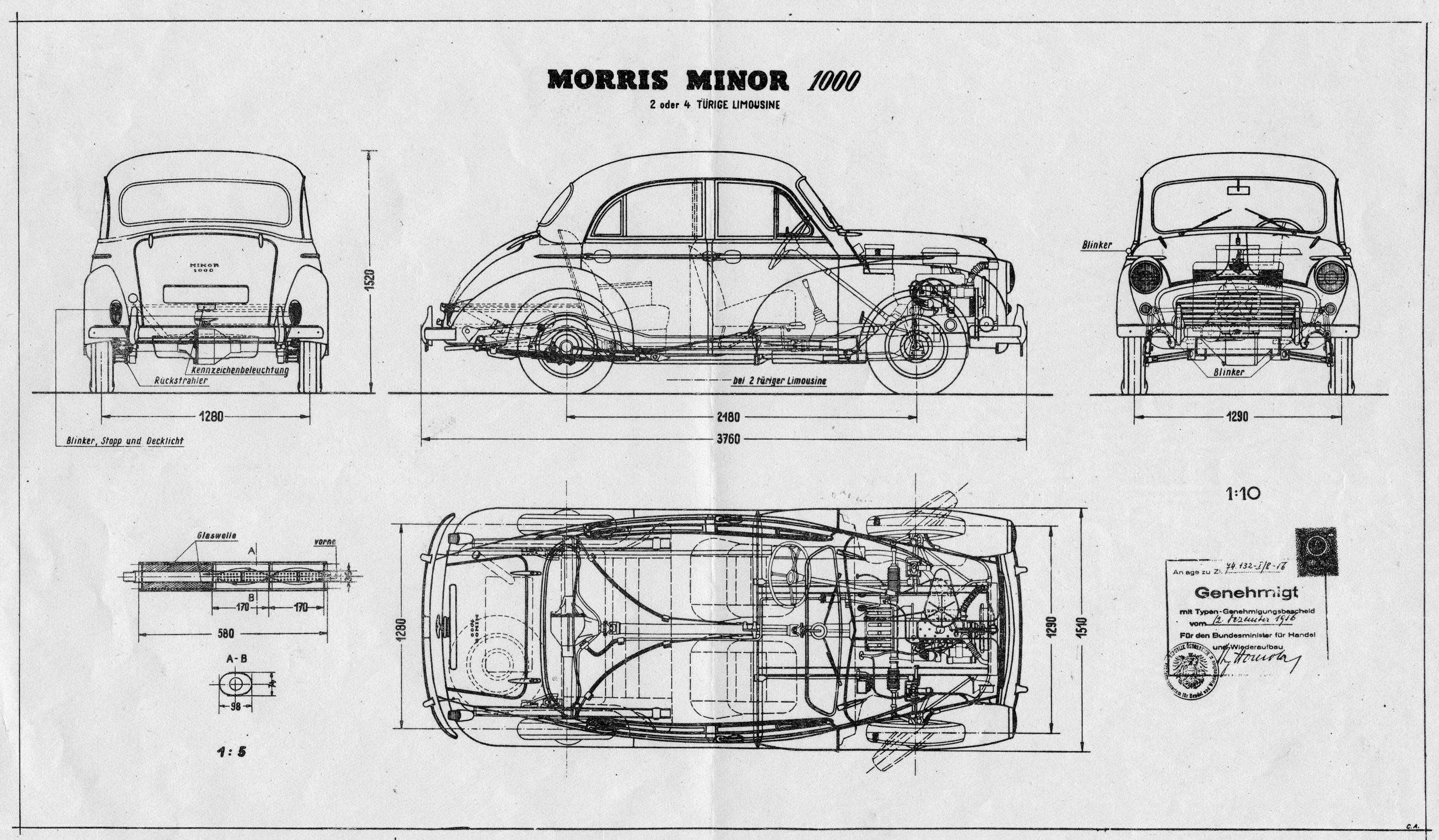

The brilliant little car that symbolised Britain's emergence from post-war austerity celebrated a remarkable milestone 50 years ago. A distinctive profile with an emphatic "glasshouse"; signature daylight openings; unitary construction; fuss-free panels; confident surfaces; restrained details; a hint of aerodynamic purpose with the headlights neatly buried beside the front air intake; understated intelligence and functionality; bold, sculpted wings unencumbered by visual clutter; a driver's delight. Is this the new Audi? No, it is the Morris Minor of 1948, which 50 years ago today reached a milestone when the millionth car rolled off the assembly line. Yet 10 years later it went out of production – and a vintage chapter of English social and industrial history closed.

Has any other English machine ever been treated to such respectful affection as the Minor? This soft-looking car makes even hard men wistful. Here is that unusual thing which, for reasons neuro-aestheticians must one day research, inspires universal delight. Is it the shape itself that affects the emotions or the dense cloud of associations swirling around it? Probably a bit of each.

It was planned as the Morris Mosquito, a reference to the sophisticated de Havilland warplane and a reminder that the Minor was conceived in an austere age of rationing and privation, relieved only by a mood of wary and bruised post-war optimism. In 1948, the Festival of Britain's playful modernism was still three years away and it was not only grim up north, it was grim down south and east and west as well. Because it was a well-meant antidote to misery – even if the first versions did not have a heater – we love the Morris Minor and the dreamworld it represents.

When the new car appeared at the Earls Court Motor Show, Elizabeth David was still researching her Mediterranean Food, whose near pornographic account of garlic, oil and lemon represented a fantasy world accessible only in the imagination to a public sustained by a regime of beige soup and gristly grey rissoles. The Minor, like tomato pasta, was to be a part of Great Britain's colourful tomorrow. Curiously, food metaphors have pursued its career. It was often, if lazily, described as bearing a morphological similarity to a jelly-mould. And Morris's proprietor, Viscount Nuffield, said, in the lordly style of an Edwardian breakfast, that it looked like a poached egg. Its designer was the man Nuffield called "Issi what's his bloody name". We know him as Sir Alec Issigonis, a true rival to Ferdinand Porsche, Dante Giacosa and Pierre Boulanger.

In the popular imagination the Morris Minor is the car of schoolmasters, district nurses, midwives, openly Anglican vicars, helpful rural grocers and men wearing hats who are, generally, not in a hurry. If the staid institution of English afternoon tea were motorised, it would look like this. The Minor is a symbol of a gracious England unspoiled by sodium lights, bypasses, tower blocks, KFC and greedy consumerism. This England was a fable maybe, but fables are often more interesting than facts. If a car had ever appeared on the cover of one of those Batsford "Face of Britain" guidebooks with their winsome and sentimental Brian Cook watercolours of rolling downs, fluffy clouds and church spires, it would have been a Morris Minor, surely the industrial equivalent of a drover's cart.

But that misunderstands the car's cosmopolitan culture. Chief influences on the Morris Minor's aesthetic were American and it is one of the beguiling curiosities of design semantics that so quintessentially English a product as the Morris Minor was, in fact, the work of an engineer born in Izmir – in those days Smyrna – to Greek and German parents. Alec Issigonis arrived in London, aged 17, after the Great Fire of Smyrna of 1922 stimulated an exodus of the city's Greek professional classes, and enrolled at Battersea Poly. But he was always an intuitive engineering designer, not an academic one. By all accounts, Issigonis was headstrong, determined, inflexible, dogmatic and difficult; one of those people who took rather than gave praise. He prized creativity, most especially his own, above discipline or economy and was happy to call himself "Arrogonis".

As a young man, Issigonis raced an Austin 7 that he had extensively modified to include independent suspension with rubber springs (a feature that his good friend Alex Moulton would later develop for the Mini). In this way, Issigonis enhanced his taste for competition as well as his preference for experimentation over theory: mathematics, he averred, suffocated the creative spirit. Still, in Britain's sclerotic and complacent motor industry, these traits were survival characteristics, not symptoms of Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

Issigonis joined Morris Motors of Cowley in 1936, working at first on advanced suspension systems. His concept for the Morris Mosquito was even more radical than the production car: four-wheel independent suspension and a sophisticated flat-four "boxer" engine were intended, but both these features were value-engineered out of the specification by Brummie penny-pinchers, although a ghost of the latter remains in the extravagantly huge engine bay. Assisted by the splendidly named Vic Oak and Reg Jobs, Issigonis man-handled and will-powered the car into existence. The Mosquito name was dropped and "Minor" adapted from a pre-War Morris tourer : the sole concession to Morris tradition. Even at immediate pre-production stage Issigonis was still interfering. Sensing a problem of proportions, he insisted the prototype be cut in half lengthways and a 10 in gusset inserted from bow to stern.

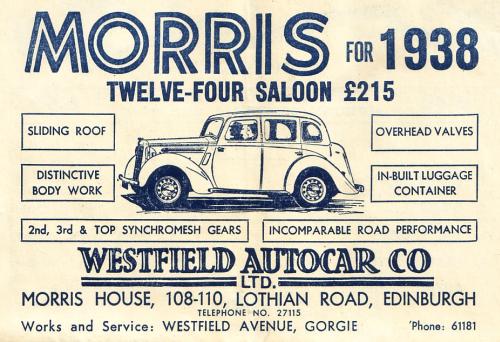

Early advertisements declared; "The new Morris Minor makes the most of your petrol, goes farther on a tankful. Traditional Morris reliability and low maintenance are inherent in this modern design." Tactfully, performance was not mentioned: the Series One could not quite reach 60 miles per hour and took about half the shipping forecast to reach 50. Still, the light weight of Issigonis's structure, augmented by crisp steering, contributed to exhilarating driving dynamics. A motoring journal said the Minor was "one of the fastest slow cars in existence". In a nice historical quirk, the 1948 Earls Court Motor Show was also the launch of the Jaguar XK120, which was the fastest fast car in existence. So the Minor and the XK120 bracketed the consumer possibilities of the Fifties just as their successors, the Mini and the E-Type, did a decade later.

The Morris Minor was the first truly sophisticated English popular car, the equivalent of (and at least as good as) the Volkswagen, Citroën 2CV and Fiat 500, but the huge potential of Issigonis's advanced design was never fully realised by its makers. BMC was formed from the merger of Morris and Austin in 1952 and became one of the first English manufacturers to adopt US-style automated manufacturing technology, but always under-invested in production, so never achieved economies of scale and never accumulated funds progressively to develop the design in the way that Volkswagen did the Beetle. And, in any case, by the mid-Fifties, Alec Issigonis was diverted by his next project, XC9003, the car that became the ineffable Mini. Still, by 1961 a million Minors had been made: a short celebration run was put on sale with 1000000 badges on the bootlid and finished in a fetching King's Road lilac with white upholstery to match mini-skirt and boots.

If we see the Morris Minor as dull, we misread it. It is a wonderful palimpsest of national vices and virtues: great ingenuity fretting against bovine conservatism. Cut a Minor in half, as Issigonis did, and you get a cross-section of national life. Like the hopelessly optimistic aerospace projects that were its contemporaries, the Minor was a design of genius compromised by crabbed, mean and unimaginative management. So, as in so much of what remains of mid-century modern Britain, it is both heroic and elegiac. Ian Nairn, our greatest architectural writer, used a Minor Convertible in his pioneering television travelogues. Here it acquired an almost human character, as all great machines do. Indeed, there is surely something in the car's name that catches a whiff of our national affair with snobbery. There never was a Morris Senior, but "Morris Minor" sounds like a greeting from a prep-school master. Let's not forget that there was at the time also a Ford Prefect.

Strange to say for something that acquired a reputation for essential Englishness as fixed and grave as tea on the vicarage lawn, John Betjeman never wrote about the Morris Minor. Instead, the only modern car he poetised was the Ford Cortina, a Detroit miniature named after a Dolomites ski resort that went on sale the year after the millionth Minor and long outlived it. That was a sign of the times that were. A sign of the times that now are is a bleak Alec Issigonis Way in the Oxford Business Park near the site of the long-shuttered Cowley factory where they planned the Morris Mosquito. BMW's Mini, a fine car, but a travesty of Issigonis's functionalist design principles, is made not far away.

Issigonis will always be remembered for the Mini, often considered the most ingenious and influential car ever built. But he preferred the Morris Minor. And who would argue with Arrogonis?